A HISTORY AND

DESCRIPTION

BY

FRANK REDE FOWKE

LONDON

G. BELL AND SONS, LTD.

1913

CHISWICK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

PREFACE.

IT is nearly a quarter of a century since the following comments on the Bayeux Tapestry were published. Their adoption, unknown to me, by the Conservateur du Depot Legal au Ministere de l'Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts, M. Jules Comte, as the basis of his "Tapisserie de Bayeux," was a flattering recognition of my labours. My original work, which contained a series of illustrative appendices, was costly, and, being no longer obtainable, it is sought to supply its place. The present volume, confined to a history of the tapestry, and to an explanation of the incidents which it depicts, appears in a more accessible form.

In preparing the plates, advantage has been taken of a method of photographic reproduction recently invented by Count Ostrorog. This method avoids the employment of a "mesh," and consequently obviates the well-known chequered appearance in the picture which is inseparable from the ordinary "process-block."

Frank Rede Fowke.

1898

LIST OF PLATES.

| I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. VIII. IX. X. XI. XII. XIII. XIV XV. XVI. XVII. XVIII. XIX. XX. XXI. XXII. XXIII. XXIV. XXV. XXVI. XXVII. XXVIII. XXIX. XXX. XXXI. XXXII. XXXIII. XXXIV. XXXV. XXXVI. XXXVII. XXXVIII. XXXIX. XL. XLI. XLII. XLIII. XLIV. XLV. XLVI. XLVII. XLVIII. XLIX. L. LI. LII. LIII. LIV. LV. LVI. LVII. LVIII. LIX. LX. LXI. LXII. LXIII. LXIV. LXV. LXVI. LXVII. LXVIII. LXIX. LXX. LXXI. LXXII. LXXIII. LXXIV. LXXV. LXXVI. LXXVII. LXXVIII. LXXIX. |

King Eadward. |

HISTORY OF THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY.

THE earliest known mention of this interesting work is made in an inventory of the ornaments of the Cathedral of Bayeux, taken in the year 1476. The preamble of this document is subjoined, [1] together with two entries from the third chapter and one from the fifth, as these passages are frequently cited by those who have written of the tapestry.

[1] Inventaire des joyaulx, capses, reliquiairs, ornemens, tentes, paremens, livres, et autres biens apartenans a l'eglise Nostre-Dame de Bayeux, et en icelle trouves, veus et visites par venerables et discretes personnes maistre Guillaume de Castillon, archidiacre des Vetz, et Nicole Michiel Fabriquier, chanoines de ladite eglise, a ce deputez et commis en chapitre general de ladite eglise, tenu et celebre apres la feste de sainct Ravent et sainct Rasiph, en l'an mil quatre cent septante-six, tres reverend pere en Dieu Mons. Loys de Harecourt, patriarche de Jerusalem, lors eyeque, et reverend pere maistre Guillaume de Bailleul, lors doyen de ladite eglise ; et fut fait ce dit inventaire en mois de septembre par plusieurs journeees, a ce presens les procureurs et serviteurs du grand cousteur de ladite eglise, et maistre Jehan Castel, chappellain de ladite eglise et notaire apostolique ; et icy est redige en francois et vulgaire langage pour plus claire et familiere designation desdits joyaulx, omements et autres biens, et de leurs circonstances, qu'elle n'eust pu estre faicte en termes de latinite, et est ce dit inventaire cy-apres digere en ordre, et disigne en distinction en six chapitres. . . . .

Ensuivent pour le tiers chapitre les pretieux manteaux et riches chapes trouves et gardes en triangle qui est assis en coste dextre du pulpitre dessous le crucifix.

Premierement ung mantel duquel, comme on dit, le due Guillaume estoit vestu

quand il epousa la ducesse, tout d'or tirey ;

semey de croisettes et florions d'or, et le bort de bas est de or traict a ymages

faict tout environ ennobly de fermailles d'or emaillies et de camayeux et autres

pierres pretieuses, et de present en y a encore sept vingt, et y a sexante dix

places vuides ou aultres-foiz avoient este perles, pierres et fermailles d'or

emaillies.

Item. — Ung autre mantel duquel, comme l'en dit, la ducesse estoit vestue

quand elle epousa le due Guillaume, tout semey de petits ymages d'or tire a

or fraiz pardevant, et pour tout le bort de bas enrichiz de fermailles d'or

emaillies et de

camayeux et autres pierres pretieuses, et de present en y a encore deus cens

quatre-vingt-douze, et y a deus cens quatre

places vuides ausquelles estoient aultres-foiz pareilles pierres et fermailles

d'or emaillies. . . .

Ensuivent pour le quint chapitre les tentes, tapis, cortines, paremens des autels et autres draps de saye pour parer le cueur aux festes solonnelles, trouves et gardes en le vestiaire de ladicte eglise.

Item. — Une tente tres longue et etroite de telle a broderie de ymages

et escripteaulx faisans representation du conquest

d'Angleterre, laquelle est tendue environ la nef de l'eglise le jour et par

les octaves des Reliques. [At this date the feast of the Relics was kept on

the 1st July]

2

On the 12th May, 1562, the cathedral was pillaged by the Calvinists, who committed the most horrible devastations. During this rising the clergy handed over many of their treasures to the municipal authorities for safe keeping, and M. Pezet has conjectured that the tapestry was placed for safety in the Town-hall, and carried thence by the mob. The Bishop of Bayeux, in

3

his report upon this occasion, 19th August, 1563, mentions the preservation of some tapestry, and the loss of "une tapisserie de grande valeur," which M. Pezet conceives to relate to the Bayeux tapestry missing from the time of its abstraction by the populace up to that date. This opinion appears erroneous, for the Bishop states that the missing hangings were used to surround the choir on solemn occasions, and that they were composed of cloths of different colours slid upon a cord. Whilst the tapestry is correctly described in the inventory as telle {i.e. toile) d broderie, and as used to decorate the nave.

Whether or not it was missing in these troublous times, it was soon afterwards in possession of the ecclesiastical authorities, being used as a festal decoration for the nave of the cathedral. Here it remained obscure and forgotten, save by those who lived within the walls of Bayeux, until, in the year 1724, a drawing which had formerly belonged to M. Foucault, Ex-intendant of Normandy, and a collector of antiquities, was presented to M. Lancelot, a member of the Academie des Inscriptions, by the secretary of that institution.

On the 21 st July of that year M. Lancelot read a paper upon the drawing, but was ignorant of what it actually represented. He had failed, he said, to discover whether the original was a bas relief, a sculpture round the choir of a church, upon a tomb, or on a frieze — if a fresco painting, stained glass, or even a piece of tapestry. He saw that it was historical, that it related to William, Duke of Normandy, and the conquest of

4

England, and conjectured that it formed part of the Conqueror's tomb in the church of St. Etienne de Caen, or of the beautiful windows which are said to have formerly existed in that abbey. Following up these speculations, he caused investigations to be made at Caen, but his researches were entirely without success.

Father Montfaucon, a Benedictine of Saint-Maur, was more fortunate. Upon reading Lancelot's memoir he at once perceived the value of this curious representation, and determined to leave no stone unturned till the original was discovered. In the first volume of his "Monumens de la Monarchic Francoise," which appeared in 1729, he gave a reduction of M. Foucault's drawing in fourteen double plates, and added a double plate, divided into four parts, with the whole of the then-discovered work, drawn to a small scale. He saw that this fragment was but the commencement of a long history, and he therefore wrote to the Benedictines of St. Etienne de Caen and of St. Vigor de Bayeux to inquire if they were acquainted with any such monument. The Reverend Father Mathurin l'Archer, Prior of St. Vigor de Bayeux, answered that the original was a piece of tapestry, preserved in the cathedral, about thirty feet in length (nearly thirty-two English feet), and one foot and a-half broad, and that they had another piece of the same breadth continuing the history, the whole being two hundred and twelve feet long (nearly two hundred and twenty-six English feet). He copied all the inscriptions, and sent them to Montfaucon, who

5

saw that the entire monument was now discovered.

Montfaucon sent a skillful draughtsman named Antoine Benoit to copy the tapestry, with instructions to reduce it to a given size, but to alter nothing. At the opening of the second volume of his "Monumens de la Monarchic Francoise," published in 1730, Montfaucon engraved the whole history in this reduced form, [1] accompanied by a commentary upon the Latin inscriptions which throughout explain the intention of the figures represented in the different compartments, and M. Lancelot now composed a second memoir, which was read in 1730. It will be seen that at the time of its discovery by Montfaucon the tapestry was in two pieces, the first ending at the word Hie of the inscription, Hic venit nuntius ad Wilgelmum Ducem, and the join, in spite of the beautiful manner in which it has been made, may still be detected. [2] At this period, too, the extremities began to suffer, and in order to save the work from destruction, the chapter caused it to be lined.

The interest awakened by the discovery of the tapestry was not confined to

France. In 1746 Stukeley wrote of it as "the

noblest monument in the world, relating to our old English History." He

was followed by the learned antiquary Dr. Ducarel, who gave an account of the

tapestry in the appendix to his "Anglo-Norman Antiquities,"

[1] These plates are, however, lamentably inaccurate.

[2] M. Lechaude-d'Anisy remarks upon the absence of any sign of a join.

6

published in 1767, where he reproduced the drawings given by Montfaucon, and printed an elaborate description which had been drawn up some years previously, during a residence in Normandy, by Mr. Smart Lethieullier. Dr. Ducarel tells us that when he was in Normandy the tapestry was annually hung up on St. John's Day, and that it went exactly round the nave of the cathedral, where it continued for eight days. This mode of decorating the cathedral of Bayeux was a most ancient custom, as we learn from its statutes, which declare that, "II est bon de savoir que le matin du samedi de Paques, avant d'appeler les dignitaires et les chanoines au service, on pare le tour de l'eglise, dans l'interieur, avec des tapisseries propres, au-dessous desquelles, entre le choeur et l'autel, on place des coussins et des draps de soie les plus beaux qui se trouvent dans l'eglise. . . . L'eglise se pare depuis la fete de Paques jusqu'a le Saint-Michel, en septembre." When not employed as a decoration for the nave, the tapestry was carefully preserved, in a strong wainscot press, in a chapel on the south side of the cathedral.

Before we again hear of it the tapestry had passed through great dangers, and had nearly perished; but, as in 1562, it escaped the revolutionary disorders by little short of a miracle. Kept in the depositories of the cathedral it remained intact, even during the events of the year 1792, until the day when the invasion of France called all her sons to arms. At the first sound of the drum in the town of Bayeux, which had already furnished a numerous contingent, rose the

7

local battalion. Amidst the tumult of sudden departure, carts were improvised to transport the military equipage. One of these conveyances needed a covering; canvas was wanting; the tapestry was suggested as suitable for the purpose; and the administration pusillanimously ordered its delivery. It was brought and placed on the waggon, which was already en route, when M. le Forestier, commissary of police, learning the state of affairs, ran to the District Directory, of which he was a member, and himself issued the order to bring it back. This was no sooner done than he snatched the tapestry from its perilous position, provided some stout canvas to supply its place, and committed the treasured embroidery to the security of his own study.

Some of the citizens, viz. MM. Moisson de Vaux, J. B. G. Delaunay, ex-deputy of the States-General, Bouisset, afterwards professor of literature at the Lyceum of Caen, with Le Brisoys-Surmont, an advocate, as secretary, now formed themselves into a commission for the protection of works of art in the district of Bayeux. They at once demanded the delivery of the tapestry, which they obtained in time to save it from a new danger. For from a letter dated "4 Fructidor an II" (21st August, 1794), we learn that "un zele plus ardent qu'eclaire avait ete sur le point de faire lacerer dans une fete civique cet ouvrage auquel on n'attachait plus d'autre merite que d'etre une bande de toile propre a servir au premier usage."

So jealous was this commission of the safety of the tapestry, that it was not mentioned in their

8

first catalogue, probably from fear lest it should be wrested from their custody, since in a letter of the "10th Frimaire an XII" (30th November, 1803) they speak of the vigilance with which they had watched over this national monument, and the opposition that their great solicitude had oft-times raised against its removal from the town.

It is not known for certain where the tapestry was kept during the time that it was in the custody of the commission, but as the books of the religious communities suppressed at the time of the revolution were deposited in the college, it is probable that the tapestry found a similar resting-place.

On the "29 Brumaire an XII" (19th November, 1803) the prefect of Calvados informed the commission that Bonaparte, then First Consul of France, desired the exhibition of the tapestry at the Musee Napoleon. To this wish the commission deferred, and it was deposited in the national museum for public inspection.

The First Consul himself went to see it, and affected to be struck with that particular part which represents Harold on his throne at the moment when he was alarmed at the appearance of a meteor which presaged his defeat : affording an opportunity for the inference that the meteor which had then been lately seen in the South of France was the presage of a similar event. [1]

At the time of this exhibition, M. Denon, director-general of the Musee Napoleon, caused an

[1] This meteor was seen in the south of England, 13th November, 1803, and particulars of it are recorded in the "Gentleman's Magazine," vol. lxxiii. part 2, pp. 1077-1120.

9

explanatory hand-book to be prepared, entitled "Notice historique sur la Tapisserie brodee de la reine Mathilde, epouse de Guillaume-le-Conquerant." [1]

The exhibition was popular : so much so, that three authors of vaudevilles, much renowned in that day, MM. Barre, Radet et Desfontaines, composed a one-act comedy in prose, entitled, "La Tapisserie de la reine Mathilde," which was produced at the Theatre du Vaudeville. In this piece Matilda, who had retired to her uncle Roger during the contest, was represented passing her time with her women in embroidering the exploits of her husband, never leaving her work except to put up prayers for his success. It related to passing events, and was of a very light character, as all such pieces are, but contained nevertheless many witty strokes, and some ingenious allusions to the projects of Napoleon.

When the time for the restoration of the tapestry to Bayeux arrived, more than one voice was raised in favour of its retention in Paris; but it was returned, after a hasty copy of it had been made by M. Denon, to the municipality of the town which had preserved it so well throughout all vicissitudes, with the following letter : —

"Paris, le 30 pluviose, an XII (18th February, 1804)." Denon, membre de l'lnstitut National, directeur-general du musee Napoleon, et de la

[1] This notice forms a brochure in 12 mo of forty-six pages, of which two other editions exist; one in 4to, with Lancelot's plates, coloured; the other published at Saint-Lo, in 1822, by Elie.

10

reconnaissance des medailles, au sous-prefet de l'arrondissement de Bayeux.

"Citoyen, —

"Je vous renvoie la tapisserie brodee par la reine Mathilde, epouse de Guillaume-le-Conquerant. Le premier consul a vu avec interet ce precieux monument de notre histoire; il a applaudi aux soins que les habitants de la ville de Bayeux ont apporte depuis sept siecles et demi a sa conservation. II m'a charge de leur temoigner toute sa satisfaction et de leur en Conner encore le depot. Invitez-les done, Citoyen, a apporter de nouveaux soins a la conservation de ce fragile monument, qui retrace une des actions le plus memorables de la nation francaise, et consacre pareillement le souvenir de la fierte et du courage de nos aieux. J'ai l'honneur de vous saluer.

"Denon."

Incited by this letter to renew their zealous precautions on behalf of their trust, the Municipal Council of Bayeux held a deliberation 24th Ventose, an XII (13th March, 1804). At this meeting it was decided that the tapestry should be deposited in the college library, and the director was charged to watch over it with the greatest care, the mayor giving his supervision. Remembering its ancient use, the council further directed "that it be hung in the parish church during fifteen days in the finest part of the year" — a concession to the clergy to which I cannot discover that effect was ever given.

11

Nor does it seem that the decision to deposit it in the college was adhered to, as it was quickly transferred to the H6tel de Ville, where the mode of its exhibition to the curious was to wind it from one cylinder on to another, after the manner of a panorama. This barbarous mode of showing it must infallibly have caused its destruction in a very short time; yet it continued with but slight protest under the Empire, the Restoration, and the first years which succeeded the Revolution of 1830.

From the new degree of publicity given to the tapestry by its exhibition in Paris, its origin again became the subject of discussion; and in 1812 the Abbe de la Rue, professor of history in the Academy of Caen, composed a memoir, subsequently translated and annotated by Mr. Francis Douce, [1] in which he contended that the manufacture of the tapestry should have been ascribed to the Empress Matilda, and not to the wife of the Conqueror.

The next notice of the tapestry is comprised in a short letter, dated 4th July, 1816, from Mr. Hudson Gurney, printed in the "Archaeologia." [2] Mr. Gurney had seen the tapestry at Bayeux in 1814; it was, he says, then kept in the Hotel of the Prefecture, [3] coiled round a machine like that which lets down the buckets in a well, and was shown to visitors by being drawn out over a table.

[1] "Archaeologia," vol. xvii. p. 85.

[2] Ibid. vol. xviii. p. 359.

[3] This is an error; the prefecture is at Caen — Bayeux is a sous-prefecture.

The building was the Hotel de Ville, where the tapestry was deposited in 1804.

12

Mr. Dawson Turner, writing some two years later, adds that the necessary rolling and unrolling were performed with so little attention, that it would be wholly ruined in the course of half a century if left under its then management. He describes it as injured at the beginning, as very ragged towards the end, where several of the figures had completely disappeared, and adds that the worsted was unravelling in many of the intermediate parts. [1] At this time the tapestry was known as the Toile de St.-Jean, which is explained by what Ducarel has said, that it was formerly exhibited upon St. John's Day. Remembering this its ancient use, the clergy, in 1816, claimed its restoration to the cathedral. To this request, however, the Municipal Council refused to accede, alleging that it had been returned to the inhabitants, who had never lost sight of it, but had preserved it through the exertions of their representatives. With the civil administration, then, the tapestry still remains.

In the same year that the clergy claimed the tapestry, the Society of Antiquaries of London despatched that excellent and accurate artist, Mr. Charles Stothard, to Bayeux, to make drawings and he brought home two small pieces of the tapestry. [2] Within two years he completed the best copy of the tapestry that had been produced,

[1] "Account of a Tour in Normandy," by Dawson Turner, 2 vols. 8vo,

London, 1820, vol. ii. p. 242.

[2] One fragment was, in 1825, seen by M. Allou, of the Societe Royale des Antiquaires

de France, in the library of Dr. Meyrick. "Les anciennes Tapisseries Historiees,"

par Achille Jubinal, 2 vols, oblong folio, Paris, 1838-39, vol. i. p. 16.

13

which will be found in the sixth volume of the "Vetusta Monumenta."

The appearance of the first portion of these drawings gave rise to some remarks [1] (dated 24th February, 1818) by Mr. Amyot, intended to refute the idea that Harold had been sent to Normandy with an offer of the succession to William, which idea the pictures of the tapestry had been supposed to confirm.

These were followed by Mr. C. Stothard's own observations while at Bayeux, pointing out such circumstances as presented themselves to his notice during the minute investigation to which he necessarily subjected the tapestry. Mr. Amyot then took up a defence of the early antiquity of the tapestry, in which he invalidates the objections of the Abbe de la Rue to the opinion which makes the tapestry coeval with the events that it records.

In 1835 the Municipal Council began to occupy themselves with the idea that a permanent resting-place for the tapestry should be provided, and they then decided that it should be removed to that place which it now occupies.

Dr. Bruce saw the tapestry about this time, and says that it was then exhibited in eight lengths up and down the room in which it was kept. I do not know if the learned doctor means that it was cut into eight parts or folded backwards and forwards; [2]

[1] " Archaeologia," vol. xix. p. 88.

[2] This latter seems to be intended, as the Abbe Laffetay describes it as "se

repliant sur elle-meme." — Notice Historique et Descriptive sur la

Tapisserie dite de la Reine Mathilde, 8vo, Bayeux, 1874, p. 17.

14

but, at any rate, nothing was lost, and the tapestry, as far as it has come down to us, is complete.

At a meeting of the Administrative Council of the Society for the Preservation of French Historical Monuments, held 30th January, 1836, Mr. Spencer Smith announced that he would shortly call the attention of the council to the tapestry of Queen Matilda at Bayeux, and offer recommendations as to the mode of its exhibition to visitors. The tapestry was gaining friends, its dangers seemed past, and men vied with each other who should most contribute to its well-being. But not content with the assurance of its safety, they were anxious to satisfy sceptical minds; and on the 15th February, 1840, we find M. de la Fontenelle, [1] together with several of his fellow-labourers of the "Revue Anglo-Francaise," about to form a commission of archaeologists composed half of English and half of French savants, to give a final opinion as to the age of the tapestry. It does not appear that this commission issued any report, nor is it by any means certain that it was ever really formed.

In 1840 we find, in the "Bulletin Monumental," [2] a report made by M. Pezet, President of the Civil Tribunal, to the Municipal Council of Bayeux, on behalf of the commission charged to take measures for the safety of the tapestry. In this report he announces that the building erected by the town for the reception of the treasured relic approached

[1] "Bulletin Monumental, public par la Societe Franchise pour la Conservation

des Monuments," 8vo, Paris, Rouen, Caen, 1834, et seq. vol. vi. p. 44.

[2] Ibid. vol. vi. p. 62.

15

completion, the masons' work was completed, and the wainscoting commenced.

In 1836, Mr. Bolton Corney printed his "Researches and Conjectures on the Bayeux Tapestry," as a brochure of sixteen pages, and, after castigating its critic in the "Gentleman's Magazine" of the following year, issued a second "revised and enlarged" edition in 1838. Not content with extirpating the tradition which ascribed the tapestry to Queen Matilda he discredited the antiquity of the work itself, seeking to show that its execution before 1206 was impossible, by some questionable arguments which invited retort.

In 1841 M. de Caumont communicated to the Institut des Provinces a notice in refutation of Mr. Bolton Corney's remarks, and an extract from this notice was published the following year, entitled "Un Mot sur les Discussions relatives a l'Origine de la Tapisserie de Bayeux." [1]

The Society for the Preservation of French Historical Monuments held a meeting at Caen, 12th May, 1853, at which M.de Caumont reported that the Bayeux Tapestry had received aid to the extent of 5,000 francs [2] (£200).

The tapestry was not shown in a settled and permanent manner in the place which it now occupies until 1842. M. Ed. Lambert, librarian of the town of Bayeux, was named custodian of the tapestry, and he it was who undertook the task of superintending its re-lining; nor did he stop here, for, guided by the holes left by the needles, by the

[1] "Bulletin Monumental," vol. viii. p. 73.

[2] Ibid. vol. xix. p. 378.

16

fragments of worsted adhering to the canvas, and by drawings executed at earlier dates, he successfully restored certain portions which had suffered from age or from the friction of the cylindrical method of exhibition.

Since the above date the tapestry has been continuously shown to the public in the same manner as at the present time, and its history during this period of repose would be but a catalogue of savants, artists, and illustrious personages who, from every corner of the world, have made a pilgrimage to Bayeux.

The tapestry was not, however, to pass its old age without some renewal of danger, for in 1871 the Prussians were so near the town as to cause most serious alarm to the authorities for the safety of their precious treasure. The tapestry was taken from its case, so rapidly that many of the sheets of glass under which it was kept were broken; it was then tightly rolled up and packed into a cylindrically-shaped zinc case, the lid of which was soldered down. What next ensued is a secret which the authorities desire to keep; for, though they trust never again to be obliged to resort to a like expedient, they wisely remark that they know not what of danger the future may have in store for the tapestry, nor do they think that the proper moment has arrived to publish their hiding-place.

On the 3rd of August, 1871, the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education authorized Mr. Joseph Cundall to proceed to Bayeux to consult with the authorities and endeavour to obtain

17

permission to make a full-sized photographic reproduction of the tapestry. He was successful in his mission, and Mr. E. Dossetter, a skilful photographer, was despatched to Bayeux to commence the work, which he completed in the following year.

The local authorities courteously rendered every assistance, M. Marc, the mayor, M. Bertot, the deputy-mayor, and the Abbe Laffetay, the librarian, vieing with each other in their obliging attentions. The work was, however, attended with great difficulty, for, although the custodians finally permitted the removal of the glass, pane by pane, so as to free from distortion the portion of the work under manipulation, they would in nowise consent to the removal of the tapestry from its case. The tapestry is carried first round the exterior and then round the interior of a hollow parallelogram, and the room in which it is shown is lighted by windows at the side and at one end, so that the difficulty of cross lights and dark corners had to be overcome as far as possible; nor this alone, for the brass joints of the glazing came continually in the way of the camera, and great credit is due to Mr. Dossetter for the ingenious devices by which he successfully overcame the difficulties with which he had to contend.

Owing to the difficulties of manipulating a large camera in the comparatively small space of the chamber at Bayeux, the negatives first taken were those used for the illustrations of his work; from these transparencies were made from which negatives enlarged to both half and the full size of the original were produced. It will therefore be seen that besides the series here given two sets of

18

large reproductions exist, one the full size of the original and one half that size, both of which were published by the Arundel Society. The Lords of the Committee of Council on Education presented a copy of each of these larger sets to the town of Bayeux, in recognition of the valuable aid and courteous co-operation of the authorities.

A copy of the full-sized reproduction was coloured after the original, and exhibited at the International Exhibition of 1873 (Catalogue No. 2897 d). This copy is now preserved in the South Kensington Museum.

The South Kensington Museum purchased at the sale of Mr. Bowyer Nicholls, in 1864, that piece of the tapestry which had been brought away from Bayeux by Mr. Stothard, [1] and it was resolved by the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education that this fragment should be restored to the custodians of the tapestry. The compiler of these notes was then, August, 1872, visiting the town of Bayeux to inspect the tapestry, and was so fortunate as to be charged with the return of the relic.

[1] Mrs. Stothard has been commonly accused of abstracting this fragment; but I have it, on her authority, that it was not until 1818, the last of the three years in which Mr. Charles Stothard copied the tapestry, that she became his wife and accompanied him to Bayeux. Prior to his marriage he possessed two pieces of the tapestry which, in whatever manner he acquired them, are said to have come from a mass of rags incapable of restoration. One of these pieces he had given, before his marriage, to Mr. Douce, the antiquary, and the other formed part of the collection which, after Mr. Stothard's death in 1821 was purchased by Sir Gregory Page Turner.

19

Mode of Execution and the Materials Employed.

The Bayeux tapestry consists of a band of linen, probably originally unbleached, and which the lapse of ages has reduced to the colour of brown holland. The present length of this band is 70 metres 34 centimetres (230 ft. 9.3 in. English measure), and its width 50 centimetres (19.6 in. English measure). It formerly consisted of a single piece of linen without seam; and although at one time divided into two parts, it has now been cleverly joined together again. In the upper margin a piece of cloth of a slightly inferior quality has been added at some time subsequent to the original manufacture of the tapestry. This additional strip, which is itself of a high antiquity, is joined to the main portion by a seam; it contains no figures, but displays blue stripes, as well as simple, double, and triple crosses; and before a kind of altar, a ladder, of which the sides are terminated by a cross and a little banded standard, the staff of which is surmounted by a cross. The width of this strip is 20 centimetres (nearly 8 in. English measure), and it may have been added to facilitate the exhibition of the main work. The whole tapestry is divided into seventy-two compartments [l] or scenes,

[1] That is, following the subjects; for the different divisions or lengths are indicated by large numbers from i to 56 marked on the canvas outside the border. The form of these numbers is such that they cannot be more than a couple of centuries old. They are of no special interest, and were probably added by some custodian of the tapestry for convenience of exhibition

20

which are generally separated from one another by conventionally-rendered trees or buildings. The tapestry contains [1] representations of —

623 persons.

202 horses and mules.

55 dogs.

505 various other animals.

37 buildings.

41 ships and boats.

49 trees.

1,512 objects.

These figures are worked with a needle in worsteds of eight different colours, viz.: Dark and light blue, red, yellow, dark and light green, black, and dove colour. The intention of most of the compartments is explained by Latin inscriptions placed over them. The letters, like the figures, are stitched in worsted, and are about an inch in height. The drawing of all the objects is rude, nor has any great attention been paid to the representation of things in their natural colours. Thus horses are shown as blue, green, red, and yellow, a circumstance no doubt due to the limited number of colours at the artist's disposal. Working with flat tints, the embroiderers had no means of giving effects of light and shade; and perspective is wholly disregarded. To indicate, therefore, objects at different distances from the spectator, they

[1] "The Bayeux Tapestry, elucidated by Rev. John Collingwood Bruce." 4to. London, 1856. P. 13, note a.

21

employed worsteds of different colours; thus a green horse has his off legs red, whilst those of a yellow horse are worked in blue, and so on.

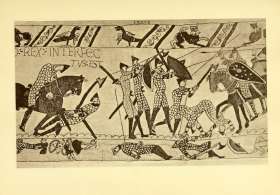

If the drawing be rude the composition is bold and spirited, and is always rendered with great truth of expression, which is at times, however, exaggerated. The really historical portion of tapestry is for the most part confined to a width of 33 centimetres 5 millimetres (13.2 in. English measure); the top and bottom forming fantastic borders, containing lions, birds, camels, minotaurs, dragons, sphinxes, some fables of Aesop and Phaedrus, scenes of husbandry and of the chase, etc. Occasionally the border is taken into the thread of the story, and it frequently contains allegorical allusions to the scenes enacting within its bounds.

The mode of working has been to cover the figures with worsted threads laid down flat side by side, and then bound at intervals by cross fastenings: seams, joints, and folds being indicated by a species of twist. The faces of persons, their hands and, when bare, their legs also, are simply outlined in red, green, or blue, the features being frequently executed in yellow.

From the above description it will be seen that historical embroidery would be a more accurate title than tapestry for this work; time has, however, consecrated the misnomer, and it is improbable that it will ever bear a different appellation.

In concluding this notice of the tapestry it is fitting to offer some opinion as to its date and

22

authorship. The chief facts upon which my judgment is based are as follows:

William and his wife were accustomed to recite their gifts to the Church, but neither the Duke on his deathbed nor Matilda in her will mentions the tapestry. This was called "La Grand Telle du Conquest d'Angleterre," when, for the first time, noticed in the inventories of 1369 and of 1476. In the latter document the canons of Bayeux recorded the traditions relating to other objects in their custody, but were silent when dealing with the tapestry, and a like silence was observed by subsequent writers. The date of its festal exhibition obtained for the tapestry the title of "La Toilette de St. Jean," and, when discovered by the Abbe Montfaucon, it was known in Bayeux as "La Toilette du Due Guillaume." The abbe recorded a tradition, as then current, that it was Queen Matilda "qui la fit faire"; this on dit was converted by Lancelot into "qui l'ait tissue elle-meme avec ses femmes," and improved by Sir Joseph Ayloffe into "by her own hands and the assistance of the ladies of her court worked in arras and presented to the cathedral at Bajeux" (sic) etc., and only after its exhibition in Paris did the tapestry acquire the designation of "Le Tapis de la Reine Mathilde."

To so late a tradition which, if actually current, was confined to a place where nearly everything was ascribed to William and his Duchess, little importance can attach.

Failing tradition, recourse must be had to internal evidence, and here (whilst there is nothing to connect the work with Matilda) the evident

23

attempt to preserve the characteristics of the principal figures (William and Eadward resembling their portraits on their seals), together with the accurate representation of eleventh century costume and of military details, which would certainly have been wanting at a later date, show it almost contemporary with the incidents depicted. Such words as AElfgyva, Ceastra and Franci suggest an English origin, but admit of the explanation that the dialect spoken in Bayeux was a mixture of Saxon and Norman, Ceastra alone remaining untraced to the Bessin dialect or its source. [1] The prominence given to Odo and to obscurer persons who were subsequently his feudatories (Turold, Vital, and Wadard), the employment of a worsted characteristic of the Bessin district, the introduction of the local form of wine barrel and of such dialectic peculiarities as Bagias and Wilgelm, the coincidence of length in the tapestry and the nave which it served to decorate, and the choice of the anniversary of the cathedral's consecration for the date of exhibition, point to the moment of its presentation by Odo, who, as bishop, alone had power to display a profane history in a sacred edifice; these facts taken together afford strong evidence of locality of origin, and suggest the probable donor. Passing the foregoing points in review, I conclude the tapestry to be a contemporary work in which Queen Matilda had no part, and that it was probably ordered for his cathedral by Bishop Odo and made by Norman workpeople at Bayeux.

[1] See remarks on p. 110.

THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY.

EDWARD REX:

King Eadward.

KING Eadward the Confessor is seated on a cushioned throne; his feet resting on a stool of three steps. A simple circlet ornamented with fleurs-de-lys forms his crown, and a similar decoration terminates the sceptre, held in his left hand. The embellishments on his ample robe are probably needlework of gold, for William of Malmesbury [1] informs us that the Lady Eadgyth was wont to embroider his state vestments after this fashion. With his right hand the King emphasizes the remarks that he addresses to two persons of rank standing before him. Of these one is undoubtedly Harold, who is taking leave of his master previous to quitting the court. Mr. Planche [2] has doubted the identity of this personage with Harold, on the

[1] Lib. ii. cap. xiii. p. 51.

[2] "Journal Brit. Archaeol. Assoc." vol. xxiii. p. 139.

26

ground that the Earl is depicted with moustaches in the next compartment, and that here the figure supposed to represent him has none. The copies of the tapestry seen by Mr. Planche must have been inaccurate, as in the original both of Eadward's auditors are moustached.

Three reasons have been assigned as the cause of Harold's departure:

I. That he begged permission to visit Normandy to release from captivity his brother Wulfnoth and his nephew Hakon, who had been given as hostages for Godwine's good conduct to King Eadward, and by him transferred for safe custody to his cousin, Duke William. [1]

II. That Harold, bound on a fishing excursion, was driven by stress of weather upon the shores of Ponthieu. [2]

III. That Harold was commissioned to assure William of his nomination as Eadward's successor to the English throne. [3]

Where authorities are conflicting it is difficult to ascertain the truth, but as the hand of the King seems to touch that of the person who is probably Harold, as if to secure a binding promise or oath, it would appear that the designer of the tapestry accepted the last theory, which tends to strengthen the Norman claim, and to show forth in darker colours the perfidy of Harold; two points which he appears to have constantly kept in view.

[1] Wace.

[2] Wm. Malm.

[3] Wm. Malm.

27

VBI: HAROLD DVX: ANGLORVM ET

SVI MILITES; EQVITANT AD

BOSHAM:

Where Harold, a chief of the English, and his knights, ride to Bosham.

Harold is called Duke of Wessex and Earl of Kent by contemporary historians; it is evident that the word Dux is here used to point him out as one of the chiefs of the English nation, and not as conveying a specific title.

This Bosham, to which they rode, had been the property of the Archbishops of Canterbury till the Earl Godwine, being very desirous to obtain this manor, and meeting the Archbishop in a certain place, advanced towards him with feigned cordiality, exclaiming, Da mihi Basium, give me the kiss (i.e. the kiss of peace), which, when the Archbishop had done, he interpreted it Boseham, and immediately took possession of it, thanking the Archbishop for his generous gift. [1]

Harold, says Dr. Bruce, is represented twice in this group; once lifting up his hand in an attitude of command, and again with his hawk upon his fist to betoken his high rank; a simpler explanation, however, would seem to be that, during the audience which is depicted in the previous

[1] "Mag. Brit." v. 492.

28

compartment, the mounted attendants have waited without the palace; they are now joined by Harold, who leads the way, his hawk perched on his fist, and his dogs scouring the country before him. It is well known to persons conversant with antiquity, remarks Mr. Ducarel, that the great men of those times had only two ways of being accoutred when they set out upon a journey, either in the habiliments of war, or of the chase. Harold, as going on an errand of peace, we find here represented in the latter. The knight's hawk and hound were cherished by him with a pride and care scarcely inferior to that bestowed on his destrier. Fabulous prices were paid for these birds, and so highly were they esteemed that the ancient statutes forbade any person giving his hawk as a part of his ransom. Amongst the Anglo-Saxons hawking was a favourite pastime, but it was reserved for the Normans to raise falconry to the dignity of a science, and thus we find that nearly all the words appropriated to the sport are old French. Severe and arbitrary laws were enacted by William, for regulating sports and protecting game, which continued to be rigidly enforced during the respective reigns of his several successors. None but persons of rank were allowed to keep hawks; and it was the Forest Charter of King Henry III. which relaxed this oppressive restriction and by which "every freeman was privileged to have eyries of hawks, falcons and eagles, in his own woods, with heronries also."

Though several hawks are introduced in the

29

course of the tapestry, in no one case is the bird provided with a hood. The hood was introduced from the East about the year 1200, and as, after its introduction, it was considered an essential part of the equipment of the bird, its absence from the tapestry is conclusive evidence of its comparatively early date. [1] We see the jesses (or leather straps attached to the legs by which the bird was held on the hand) and, I think, also, the bewits (leather rings round the legs), but no indication of the long and thick white leather glove upon which the bird was always seated in after days.

The hawks are depicted in the tapestry as of a size that could scarcely have been attained even by the gerfalcon, a bird appropriated to the use of Emperors. The size is no doubt to add importance to the bearers.

Horses were introduced into this island long before the Christian era, and employed for both warlike and domestic purposes. The crossing of the English horses with those of the Romans and subsequently, in the reign of AEthelstan, with those imported from Germany, appears to have improved the breed, for it became so prized abroad that a law was made in 930 prohibiting exportation. About the time of the Conquest a horse cost 305., a mare or colt 20s., and an untrained mare 60d. William took great pains to improve the breed by crosses with the horses of Normandy, Spain and Flanders, and in his reign the horse was first used in agricultural operations.

[1] Dr. Bruce, p. 31.

30

It will be observed that three of Harold's dogs wear collars fitted with leash-rings, and that the horses are hog-maned. Harold's horse seems to have some ornament entwined with its mane. Both saddle and stirrups are used, the former being high peaked and apparently made of wood.

It seems likely that the stirrup was a somewhat recent invention, for all the knights in the tapestry do not use them, and the only form of spur that occurs is the pryck.

ECCLESIA:

The Church.

Harold and an attendant, who is perhaps intended as a representative of the rest, [1] but who is more probably his companion of the introductory scene, enter the church of Bosham, to perform their devotions and seek a blessing on their enterprise. They gaze earnestly towards the interior, and genuflect reverentially as they cross the sacred sill. Harold's show of piety contrasting strongly with the subsequent violation of an oath taken under the most solemn circumstances was here, Dr. Bruce thinks, uppermost in the artist's mind.

Their religious exercises terminated, they adjourn to a neighbouring house, doubtless Harold's, to pass the remaining time of their stay on shore

[1] Dr. Bruce, p. 32.

31

in one of those carouses to which our Anglo-Saxon ancestors were singularly partial. In a solar or large upper hall, the place peculiarly set apart for eating and drinking, is the feast prepared. The tapestry does not show us the form of the table, but we know that it would then consist of a board laid on tressels, and covered with a cloth. [1]

This seems not to be a regular meal, since the large joint of salted meat which in those days formed the chief dish does not appear. It was probably but a hasty collation of bread and baked apples washed down with beer or wine; in bowls and horns of which they are engaged in pledging one another when a messenger announces that all things are ready for their departure. It is, however, possible that the Earl's followers are alone feasting here whilst Harold and his esquire are at their devotions, and that it is Harold's readiness to go on board which the attendant communicates.

Be this as it may, the Earl and his retinue quickly strip off their nether garments and wade to their boat, carrying the hawk and hounds. They are followed by the seamen, oars in hand, one of whom also carries an implement of which, Dr. Bruce states, [2] no satisfactory explanation has been given, and which he conjectures may be a throwstick such as was used by the ancient Egyptian fowlers. It appears to me to be simply the leash, which, having been removed from one of the dogs, is now employed to overcome its reluctance to leave the shore; the bending being

[1] Wright, "Homes of other Days," p. 33.

[2] P. 34.

32

but the artist's device to express the flexibility of the material.

The border beneath the banquet scene shows two animals engaged in licking their paws, whilst that under Harold's embarkation is illustrated with the fables of the Fox and the Crow and the Wolf and the Lamb.

HIC HAROLD MARE NAVIGAVITE ET VELIS: VENTO: PLENIS VENIT: IN TERRA: VVISONIS

COMITIS

Here Harold set sail upon the sea, and with sails filled by the wind came to the land of Count Guy.

Harold's party occupy a large boat, a smaller one towing astern. These are shown twice; once as leaving England; and again as arrived at the coast of Ponthieu, of which the above-mentioned Guy was count.

The representation of the Earl's departure is very spirited, the anchor is weighed and the boat rides on the swell, two persons with poles keep her from grounding, another prepares to set sail, and three seamen rest on their oars ready to give way at a moment's notice.

The larger vessel is but an open boat, the bow and stern of which nearly resemble each other, as

33

in the whaleboats and Maltese galleys of the present day. The single mast, apparently stepped each time that sail was made, is traversed by a yard on which the square sail is set. It is not clear if, like the smaller boat, she is furnished with thwarts for rowers, but the presence of a series of holes, answering to rowlocks, favours the supposition. A paddle over the windward quarter answers the purpose of a rudder. The sides of the vessel, which are very low, are heightened, when under sail, by an artificial bulwark, formed by the shields of the crew, locked one within the other, as we find them in the paintings of Herculaneum, and, as we see in the later scenes of the tapestry, the English were accustomed to form their "Shield-wall" in time of war.

From their form and fittings we may easily, says Lancelot, perceive that these are not fishing boats, which proves that Harold's voyage was not unpremeditated; and Dr. Bruce, supporting this view, remarks that all signs of a gale are wanting.

However this may be, the ship nears the land, a watch has been set at the mast-head, and preparations are made for coming to an anchor. Harold, who has been all this time at the helm, now takes the sheet into his left hand; three of the crew stand by the back-stays, a fourth appears to be slacking the main halliards, a fifth prepares to unship the mast, another man hauls up the boat by its painter, whilst one of his mates is engaged in stowing the sail, and two more are vigorously backing water to keep the vessel from beaching.

34

HAROLD.

Harold.

Plates VI. and VII.

Harold, in full costume, next approaches the shore in the boat, the anchor is cast, and he prepares to land. He is ready to pay his respects to the lord of the land, but the spear which he carries seems to indicate his distrust of a pleasant reception. The sequel shows that his uneasiness was not ill-grounded, and affords an illustration of the barbarous rights of nations then recognized.

HIC: APPRREHENDIT: VVIDO: HAROLDV:

Here Guy seizes Harold.

It was the custom, observes Monsieur Thierry, in his "Histoire de la Conquete," [1] of this maritime country, as of many others in the Middle Ages, to imprison and hold for ransom all strangers thrown upon its coast by a tempest, instead of rendering them any assistance. We here observe the enforcement of this right, for no sooner is Harold's parley from the boat concluded, and he and his attendant have stripped and waded ashore, than they are arrested by a follower of the Count who points to him as authority for his act.

[1] Vol. i. p. 295.

35

Whatever the nature of the conversation held between Guy and Harold previous to his debarkation may have been, the latter was induced to relinquish his spear and to land, retaining only his saxe; that weapon that was never laid aside, but, half knife, half dagger, was used at meals, laid by the hand when sleeping, and ultimately deposited in the grave of its owner. [1] With this simple weapon Harold and his follower prepare to show fight, but the Count's mounted guard, fully armed with lance, sword, and shield, renders effectual resistance hopeless, and the Earl, together with his crew, is taken captive.

Guy is here represented as plainly dressed, but well armed. A large sword hangs at his side, a basilard or hunting-knife, which a writer in the "Gentleman's Magazine" [2] erroneously conceived to be a horn, is suspended . from his saddle, and the pryck spur is on his heel. We may here point out that the Norman horses are depicted in the tapestry as larger than those of the Anglo-Saxons, and that, although the trappings are common to both nations, the uncut mane here falls on the neck, instead of being hogged in the manner already noticed as then customary in England. [3] It will be noticed that throughout the tapestry entire horses are alone represented, the same opinion as to the inefficiency of mares and geldings to perform the more arduous kinds of work appearing to have been then common which still obtains in France.

[1] Dr. Bruce, p. 42.

[2] Vol. lxxiii. p. ii, 37.

[3] "Ladies' Newspaper," 1851-52.

36

ET DVXIT: EVM AD BELREM: ET IBI EVM: TENVIT:

And led him to Beaurain and there imprisoned him.

Plates VIII. and IX.

The author of the Chronicle of Normandy, first printed in the year 1487, states that "He led him to Abbeville," but that writer is too inaccurate in other instances to be entitled to much credit here. Montreuil, not Abbeville, being then the capital of Ponthieu, and the residence of its counts, and finding, as we do, that Beaurain-la-Ville and Beaurain-le-Chateau (Castrum de Bello-ramo) were but some two leagues thence, we may safely identify them with the Belrem to which the Count is here mentioned as conducting his prisoner. [1]

The capture shown in the last plate having been effected, the party turns about and proceeds towards the Count's chateau. Monsieur Jubinal, [2] Dr. Bruce, [3] and indeed most of those who have commented upon this picture, consider that the foremost horseman is intended to represent Guy; he has, say they, now that the chances of a fight are over, resumed his cloak, and bears on his fist his hawk, since his progress is now one of peace.

[1] Ducarel, "Ang.-Norm. Antiq." Fol. London, 1767. App. p. 7.

[2] "Anciennes Tap. Hist." 2 vols, oblong fol. Paris, 1838-39, vol.

i. p. 32.

[3] Dr. Bruce p. 44.

37

His bearing is triumphant, his mantle is proudly trussed up on the shoulder, his falcon wears grillets, or bells, a mark of honour then greatly esteemed, and turns its beak forwards as ready to take flight; whilst Harold's aspect is totally different, since he is stripped of his mantle and his falcon of its grillets. The bird turning its head towards him appears to typify the unhappy condition of its master.

Before, however, endorsing the above theory it may be well to notice two or three points. The foremost rider wears a moustache and mantle, but is neither armed nor spurred. He who follows is shaven, and has no cloak, but carries the basilard and wears the pryck spur, all which corresponds with Guy's portrait in the preceding scene. The absence of grillets, if they be absent, for this is not very clearly shown in the tapestry, now simply indicates the inferiority of his rank. To my mind the moustache suffices to identify the foremost figure with Harold. This would reverse the position of the characters. Harold's followers go first, escorted by some of the Count's retainers; then comes the captive Earl; thus placed, he is under the eye of Guy, who brings up the rear with his horsemen. I do not think that I stand quite alone in this view, for it appears to have been that of a writer in the "Gentleman's Magazine." [l]

It may be noticed that whilst the foremost rider carries his falcon, as usual in the tapestry, on the left hand, his right, which in civil life seems to have been the bridle hand, is unoccupied, the reins

[1] "Gent's Mag." lxxiii. p. 1138.

38

hanging on the horse's neck. May not this be a conventional method of denoting that the rider is not going of his free will; since, at a later time, "to ride spurless" appears to have been a phrase almost equivalent to being conducted as a prisoner? [1]

VBI: HAROLD: 7 VVIDO: PARABOLANT:

Where Harold and Guy converse.

Plates IX. and X.

Harold's sword seems to have been but just returned to him, for it is shown first in the custody of one of the Count's guards, and then as held in Harold's hand as though he had not had time to gird it on. With one follower, he is introduced into Guy's presence chamber. Here the Count is seated on a throne, exhibiting the customary dog's-head ornament; the inferiority of his rank to that of a king being, seemingly, indicated by the absence of a cushion. His feet rest on a footstool of three degrees; his left hand grasps a huge sword of justice, whilst his right emphasizes his conversation with Harold, who bows slightly on entering, and appears to be expostulating. Their conversation has been supposed to relate to the amount of ransom required, which we find in this instance was very considerable. It may be that Harold's companion was his co-ambassador; that their

[1] "Athenaeum," 30th October, 1875.

39

mission from Eadward was now declared, and permission sought to acquaint Duke William of Normandy with the critical position of his cousin's vassal; but, for reasons which I give later (see p. 44), I incline to suspect here a bare announcement of the advent of the Duke's commissioners. An armed attendant touches Guy's left arm, and calls his attention to something passing without; probably to the approach of William's messengers. A man in the doorway leans eagerly forward, his antic action, and the singularity of his costume, party-coloured and vandyked, suggested to Mr. Stothard the idea that this personage is intended to represent Guy's fool or jester. [1] Dr. Bruce conceives him an unobserved witness of the interview, and that he has found means to acquaint William with the untoward position of the English. But we shall shortly see that the messenger who came to the Duke was, as his moustache indicates, a Saxon; whilst the jester, if jester he be, is here portrayed as clean shaven. They cannot, therefore, be identical, and this man may be, after all, but the messenger who announces the coming of the Norman emissaries.

[1] "Archaeologia," vol. ix. p. 189

40

VBI: NVNTII: VVILLELMI: DVCIS VENERVNT: AD VVIDONE

Where Duke William's messengers came to Guy.

Plates XI. and XII.

Two knights are sent by the Duke to treat with Guy; who, as soon as they are dismounted, receives them, and stands with a haughty air, axe in hand, to show, as has been thought, his power of life and death over his captive. The Count is partially habited in his war harness, having a tunic of scale armour beneath his mantle; an armed attendant, who stands behind him, seems to be offering counsel, whilst William's messengers press the object of their mission with great vigour.

TVROLD

Turold.

While the ambassadors confer with Count Guy, their horses are held by a personage wearing a beard, but whose shaven head sufficiently proclaims his nationality. It is commonly held that the artist intended him for a dwarf, and Miss Agnes Strickland conceives him to have been the designer of the tapestry, who modestly introduces his portrait here rather than in a more important scene, but she does

41

not furnish the grounds on which this singular speculation is based. [1] Over the head of this individual is the word Turold, and to him it has generally, but as I think incorrectly, been considered as applying. To my opinion it has been objected that if this word had related to the hindermost of William's messengers it would have been placed over his head, in the same way in which we have already seen that Harold was indicated when landing; but the objectors have overlooked the fact that the heads of the Norman knights already touch the running inscription, and that no room is left for the insertion of a name in that position. The artist has, however, been at great pains to prevent any mistake as to whom this word refers, and has taken the unusual course of enclosing it between two lines, attaching these to the back of the person whom the name is intended to indicate. This would seem to be sufficiently clear of itself, but the next compartment shows us that the messengers come on their errand unattended; and the dwarf must consequently be a retainer of the Count of Ponthieu. His name was not likely to be known to the designer of the tapestry, but with those of the messengers he would be doubtless acquainted. Turold was a common Norman name at the time of the Conquest. Aluredus (nepos Turoldi) grandson or nephew of Turold, held lands in Lincolnshire during the reigns of Eadward the Confessor and of William. A Turold was Sheriff of Lincolnshire after the Conquest, and founder of Spalding

[1] "Lives of Queens of Eng." vol. i. p. 59.

42

Abbey. His niece and heiress was Countess of Chester, and married Ivo Taillebois, the Conqueror's nephew. An Albert and a Richard Fitz-Turold are mentioned in the Domesday Book. Duke William's governor or tutor was named Turold — "Turoldus teneri Ducis pedagogus" — but he was killed shortly after William became Duke of Normandy. Finally, a Gilbert Fitz-Turold held, at the time of the survey, Watelege, which had previously been held by King Harold. This Gilbert appears to have been a feudatory of Odo. [1] Through the kindness of Monsieur Dubosc, the learned archivist of St. Lo, I saw a charter bearing the + marks of Duke William and of Turold, Constable of Bayeux. To identify him with the Turold of the tapestry offers, I think, the most satisfactory solution of this difficult point that has been as yet suggested; for it is scarcely reasonable to suppose that a man set to the menial employment of holding the horses of the Count's visitors would be specially referred to by name. The only reason that seems to have suggested the attendant as worthy of remark is his small size; but this, observation will show to have been forced upon the artist. Given the label with the name above his head, and the necessity of raising his feet to the middle distance, to suggest that he was out of earshot of the conference, and the space into which the unimportant servitor had to be compressed, was clearly defined. It is curious if the very care taken by the designer to avoid the

[1] "Journal Brit. Archaeol. Assoc." vol. xxiii. p. 141.

43

possibility of error should have conferred a posthumous glory upon the wrong man.

If my view be correct, William, perceiving the importance of securing Harold's person, sends people of condition to negotiate his release, and that one in whom the inhabitants of Bayeux would take an especial interest, their Constable, alone is named. With him they would be familiar, and it is doubtless his son whose name, as we have seen above, occurs in "Domesday" as an under-tenant of Bishop Odo.

NVNTII: VVILLELMI

William's Messengers.

Plates XII. and XIII.

A writer in the "Gentleman's Magazine" [1] considers these two ambassadors as different from those whose interview with Guy has just been noticed; and to show it, says he, the groups are separated by a species of vaulted edifice. Entreaties and remonstrances having failed to procure Harold's release, William next employs menaces. The two ambassadors are knights, who arrive on the full gallop with the lances couched; appearing to announce that their embassy is of a less amicable character than the former. This view being supported by Dr. Bruce, it is with diffidence that I advance the opinion that the order of time is here inverted, a practice by no means uncommon, and

[1] Vol. lxxiii. p. 1226.

44

of which, in the case of King Eadward's burial and death-bed (Plates xxxi., xxxii.), we shall find another example in this very work. I believe that we here see, on their journey, the same messengers whose arrival we have already witnessed, whilst the next compartment shows us their dispatch by William at the entreaty of the Saxon who has acted as Harold's envoy. I am by no means certain that this inversion of chronological sequence should not be extended to the scene of Guy's conversation with Harold and that he only has his sword restored when the Duke's envoys are at the gates. It is as if the artist would say Guy was having a conference with Harold when the arrival of the Duke's messengers was announced to him; here you see him receiving the message; this is where they were on the journey; and they were sent by the Duke, as you will see in the next section. The building, on which so much stress has been laid as separating the supposed different embassies, is doubtless but the castle of Beaurain, which the horsemen approach as they proceed on their mission.

+HIC VENIT: NVNTIVS: AD WILGELMVM DVCEM

Here the messenger came to Duke William.

Plates XIII. and XIV.

William is seated on a throne, which, with the exception of its having a cushion and the footstool

45

consisting of but two steps, nearly resembles that of Guy. He receives the suppliant Englishman, for such his moustache proclaims him, with a cheerful expression of countenance, and issues orders to two of his retinue, who turn with alacrity to obey him whilst he yet speaks. We have already seen what duty they were called upon to perform; its results were, however, of considerable importance, and a watchman, who is posted in a tree, looks eagerly forth, shading his eyes with his hand, to retain in sight as long as possible the retreating forms of the messengers.

The envoy approaches William with evident symptoms of awe; his crouching posture was construed into deformity by Montfaucon, who was therefore of opinion that it represented the same dwarf whom we have just seen holding the horses of the Norman ambassadors. This opinion was adopted by Monsieur Lechaude-D'Anisy, and even Mr. Planche goes so far as to say that the fact of one of the men-at-arms placing his hand on the head of the messenger [1] indicates a familiarity only to be accounted for by the peculiar character of the individual subjected to it. [2] These learned writers appear, however, to have overlooked the fact that the beard and shaven crown which appear as such marked characteristics of the dwarf, are not reproduced here, whilst all those of a Saxon are present.

It is a matter of dispute whether the building

[1] The hand of the man-at-arms is behind, not upon, the Englishman's head.

Compare the position of the hands of speakers and listeners in Plates

i. vii. x. xi.

xxix. xxx. etc.

[2] "Journal Brit. Archaeol. Assoc." vol. xxiii. p. 142.

46

that follows this scene forms a part of it, [1] or belongs to that which succeeds. [2] If it related to the latter, it could be but the castle of Beaurain, which, as we have already seen, was a building of a totally different character; moreover, the sentinels on the walls look towards William on his throne, whilst, had they been concerned with the transactions of the following compartment, they would hardly have turned their backs upon so important and interesting a spectacle as the meeting of their master with the powerful Duke of Normandy. Taking these points into consideration, we must, I think, regard this picture as a representation of William's castle of Rouen.

HIC: WIDO: ADDVXIT HAROLDVCD AD VVILGELMVM: NORMANNORVM: DVCEM

Here Guy conducted Harold to William Duke of the Normans.

Plates XIV., XV., and XVI.

Guy had been himself imprisoned for two years by William, and no doubt rejoiced to have in his power one whose person was of value to his powerful enemy, and who thus offered so delicious an opportunity for revenge. Having dallied with the dangerous luxury as long as he thought

[1] "Gent's Mag." vol. lxxiii. p. 1226.

[2] Jubinal, "Les anciennes Tap. Hist." vol. i. p. 33.

47

prudent, he yielded to William's menaces and the promise of a heavy ransom, and conducted his prisoner to Eu, [1] whither the Duke, with a troop of armed horsemen, was come to receive him.

Eadmer, Roger of Hoveden, and others, have stated that Guy sent Harold to William, but it will be seen that the tapestry supports the assertions of William of Poitiers, Matthew Paris, and William of Malmesbury, that the Count of Ponthieu himself surrendered Harold into William's hands, at the same time receiving the promised ransom. "Grates retulit condignas, terras dedit amplas ac multum optimas et insuper in pecuniis maxima dona." Our friend Guy was far too wary to lose sight of his valuable prisoner before an equally valuable equivalent was forthcoming.

William sits firmly on his horse, and is represented as a strongly and squarely built man — in common with Guy and Harold, he wears the -mantle of noble birth. His posture is indicative of decision of character, and we have here, in all probability, no fancy portrait of the Conqueror. [2]

Monsieur Jubinal, adverting to the remarks which he made upon the scene of Harold's journey to Beaurain, observes that his hawk is once more turned as if ready for flight, and that its grillets have been restored.

[1] "Gent.'s Mag." vol. lxxiii. p. 1226.

[2] Dr. Bruce, p. 52.

[3] Jubinal, "Les anciennes Tap. Hist." vol. i. p. 33.

48

HIC: DVXI VVILGELM; CVM HAROLDO: VENIT: AD PALATIV SVV

Here Duke William, together with Harold came to his palace.

Plates XVI. and XVII.

The word palatium is ambiguous, and we must turn to William of Poitiers for the information that it was to Rouen that Harold was escorted by William. [1] The tapestry shows us a spacious building, the roof of which is carried by seventeen semi-circular arches. The architectural features of this edifice exactly resemble those represented in manuscripts of the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries. [2] From an adjoining tower a watchman perceives the safe return of the Duke and his retinue.

No sooner are they arrived than William gives an audience to his guest, and we see the Duke seated on his throne listening attentively to a moustached person, recognized by common consent as Harold, who apparently introduces a troop of Norman soldiers.

What the subject of this conversation was we have now no means of ascertaining for certain; but, apart from a surmise which 1 make in the

[1] Willelm is a spelling found on William the Conqueror's coins; but Wilgelm,

the form adopted in the legend to this section, is undiscoverable. It, probably,

is the Bessin form of Willielm, which is the spelling used by William of Poitiers,

etc.

[2] Jubinal, "Les anciennes Tap. Hist." vol. i. p. 33.

49

following section, it has been variously conjectured as representing —

1 . Harold giving an account of his mission from King Eadward, and assuring William of his succession to the crown of England. [1]

2. The announcement of Conan's threatened invasion.

3. Harold undertaking to marry William's daughter and to give his sister in marriage to one of the Norman nobles. [2]

4. Harold praying William to send messengers to England to acquaint his friends with the news of his safe release from the dungeons of Beaurain. [3]

VBI: VNVS: CLERICVS: ET: AELFGYVA

Where a certain clerk and AElfgyva . . .

We have now reached what is unquestionably the most puzzling representation in the entire tapestry. Who is this lady, with a purely Saxon name, who is here introduced, seemingly at the gate of William's palace, with no apparent reference to anything before or after ? As yet, nothing has been detected in the contemporary chronicles which throws the least light upon this subject, and

[1] Lechaude-D'Anisy, "Description de la Tapisserie de Bayeux," royal

8vo, 1824, p. 352.

[2] Ibid. p. 353.

[3] Dr. Bruce, p. 53.

50

in the absence of facts, the wildest conjectures have been hazarded.

Many of those who have commented upon this scene seem to have been unaware that AElfgifu is a very common English name, [1] and to have fancied that it was a sort of title, meaning queen or princess. Thus Ducarel [2] says that this word seems to have been rather titular than personal, and Dr. Bruce, [3] whilst quoting Thierry [4] as his authority for its signifying a present from the genii, appears to concur in Ducarel's opinion. These writers seem to have adopted the idea of Lancelot, who argued, from the double name of Eadward's mother AElfgifu-Emma, that AElfgifu was equivalent to Hlaefdige.

Starting with the erroneous opinion that this word was synonymous with the title of queen, some writers conceive that William's duchess is here portrayed, [5] and that a secretary or officer informs her of the promise of her daughter's hand, which the Duke has just made, to Harold. But this is clearly absurd; for were the term descriptive, it is to a Saxon queen alone that it could apply. The correct titles of Harold, both before and after his coronation, are most carefully given, showing the pains taken by the designer to avoid anachronisms. So accurate an historian

[1] "History of the Norman Conquest of England," by A. Freeman, 3

vols. 8vo, London, 1867-69, vol. iii. p. 696.

[2] "Ang.-Norm. Antiq." App. p. 10.

[3] Dr. Bruce, p. 53.

[4] Thierry, "Norm. Conq." p. 41.

[5] Ducarel, "Ang.-Norm. Antiq." App. p. 10.

51

would never have called the Duchess "Queen" before her husband had ascended the English throne. [1]

Several other writers contend that one of William's daughters is here introduced to our notice, [2] but their opinions vary as to the lady's identity.

Mr. H. Gurney [3] thinks that Adeliza is represented; a devotee whose knees are said to have become horny from incessantly kneeling in prayer, and who died affianced, against her will, to Alfonso of Spain. Again another writer cautions us against such a supposition, and insists that it is on the head of her sister Agatha that a secretary lays his hand in token of her betrothment: [4] whilst Monsieur Delauney [5] asserts that it is Adela, another daughter, who was promised to Harold, and subsequently married to Stephen, Count of Blois. We need not, however, enter into their arguments, for none of these ladies could have been the "AElfgyva" of the tapestry. Wace, indeed, speaks of Harold's promised bride as Ele; but, making every allowance for the varieties of their names, we can hardly conceive that a person so conversant with the minutest details, as the designer of the tapestry undoubtedly was, should so travesty the name of one of his master's

[1] Dr. Bruce, p. 54.

[2] "Researches and Conjectures on the Bayeux Tapestry," by Bolton

Corney, 8vo (London, 1838), p. 19; "Archaeologia," vol. xvii. p. 101,

and vol. xix. p. 200.

[3] "Archaeologia," vol. xviii. p. 364.

[4] "Gent's Mag." vol. lxxiv. p. 314.

[5] "Origine de la Tapisserie de Bayeux, prouvee par ellememe, par H. F.

Delauney," royal 8vo, Caen, 1824, p. 74.

52

daughters. As she was never queen the epithet, on the supposition that it was titular, could not with propriety have been applied to her. Moreover, at the time of Harold's visit to Normandy William's daughters were but children, to whom we cannot suppose that any formal embassage would be sent.

In the opinion of Dr. Bruce, [1] the lady is Ealdgyth, the widow of Gruffydd, King of Wales, and sister to Eadwine and Morkere, Earls of Mercia and Northumberland, whom Harold married [2] shortly after his return to England, as his second wife. Her name, as written by Florence of Worcester, differs little from "AElfgiva," and as Harold's wife, even the supposed titular signification would be right. Dr. Bruce thinks that the clerk announces Harold's safety to his betrothed, who has been temporarily placed in a nunnery, and that an exhibition of the Earl's perfidy in thus dallying with his English sweetheart, at the time that he was engaging himself to another, is intended.

Harold's sister Eadgyth is here recognized by M. Lechaude-D'Anisy, [3] who conjectures that she was amongst the hostages sent to Normandy at the time of her father's rebellion, and that she now receives news of her deliverance, whilst Monsieur Thierry [4] thinks that the mysterious woman is but an embroidress, to whom a clerk gives orders to execute the tapestry.

[1] Dr. Bruce, p. 55.

[2] "Monumenta Historica," 614-642.

[3] D'Anisy, "Desc. de la Tap." pp. 353-4.

[4] Jubinal, "Anciennes Tap. Hist." vol. i. p. 33.

53

Mr. Planche [1] has pointed out that the inscription is left incomplete, and thinks that this fact, coupled with the occurrence of certain very gross figures in the border, implies a scandal which was so well known at that period as to render a plainer allusion to it perfectly unnecessary, and which, thus introduced, says Mr. Freeman, [2] goes together with Turold, Vital, and Wadard, to prove the contemporary date and authority of the tapestry.

Mr. Planche goes on to say that there were only two contemporary personages popularly designated AElfgifu, concerning whom he has been able to trace a scandal as attaching — Firstly, AElfgifu-Emma, sister of Richard II. Duke of Normandy, the Queen, first of AEthelred, King of England, and secondly of Cnut the Great, and mother by the former sovereign of Eadward the Confessor. According to some historians, she was accused by Godwine, Earl of Kent, and Robert, Archbishop of Canterbury, of being accessory to the murder of her son AElfred, and also of a disgraceful intimacy with AElfwine, Bishop of Winchester.

Secondly, AElfgifu of Northampton, the mistress of Cnut, and the daughter of the Earldorman AElfhelm, by the noble lady Wulfruna. Florence of Worcester tells us that she palmed off Swend, the son of a certain priest, upon the King as his, a like story being told in the case of Harold Harefoot, with the substitution of a cobbler for a priest as the real father. But having considered these

[1] "Journal Brit. Archaeol. Assoc." vol. xxiii. p. 142.

[2] "Norm. Conq." vol. iii. p. 699.

54

cases, Mr. Planche confesses that he is unable to connect them in any way with the picture under discussion.

We now come to the opinions of Mr. Freeman, [1] who, having examined the different views that I have recapitulated, offers certain ideas, which, whilst he owns that they are but guesses, he thinks superior to those of some others in not being absolutely impossible. He considers it possible that AElfgifu, the name assumed by Emma on her marriage with AEthelred, was the name usually adopted by foreign women who married English husbands, and that a reference to the intended marriage of Harold with William's daughter may be here proleptically or sarcastically designed. He states that AElfgifu was the name of AElfgar's widow, the mother of Harold's wife, Ealdgyth; that according to some accounts she was of Norman birth, and suggests that she might have been living in or visiting her native land at this time, and that her introduction may have reference to Harold's marriage with her daughter.